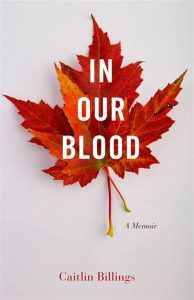

Ashley: I am very excited today. I have Caitlin billings joining me. Caitlin is a licensed clinical social worker, a therapist she’s also openly discussing her own bipolar disorder diagnosis, and hopes of normalizing these types of conversations. She’s the author of In Our Blood, thank you so much for joining me.

Caitlin: Thank you for having me.

A: Can you tell us a little bit about what In Our Blood is about?

C: Yeah. It’s been described as a combination of a coming-of-age memoir along with a reckoning of motherhood. And to me, what that means is I explored what it meant to kind of grow up in a life that many people will be able to associate with and what that was like as I grew up with depression experiences, with some traumatic experiences and then coming into my own in my late twenties, thirties, building a family, thinking that everything was pretty well under order. I got this, I got a career, I got a partner, I got two kids and then my kids started to grow up and I was dealing with my bipolar diagnosis at that time, taking a lot of different medications, struggling with depression and things had really gotten under control. My daughter, my eldest turned 12 and she began exhibiting a lot of the symptoms that I saw in myself growing up. I had to reckon with that as a mother, as a parent, as an adult, seeing this, happen in my child while simultaneously dealing with it in myself.

A: Which must’ve been extremely, extremely challenging. Can you take us back to when you started first exhibiting these symptoms and what that was like for you and maybe what that looked like?

C: Yeah. I think I really started noticing symptoms in my mid to late teens. I started having bouts of depression. I actually remember my mom taking me to see the doctor. And this was like in the early nineties. I distinctly remember him telling her and me that I just needed to get more exercise which I was like, okay, well I’m not a sports person, so I’m not sure what you’re talking about. That was the intervention I got for my depression.

A: Even if you were a sports person, you could have the exact same depression that it was really challenging back then of what conversations look like to what conversations look like now.

C: Yes, absolutely. I also had a really complicated growing up. I was adopted by my father. So I grew up knowing that I was adopted but that stirred up a lot of feelings about my identity and who I was. I didn’t know my biological father. It was also at a time where even to talk about openly being adopted was really different. Most people didn’t even know they were adopted.

A: Mind boggling when you think about it, because it’s very, very common sort of anybody maybe below the two thousands that it really was the yes, your mine and, even if you don’t look the same or don’t necessarily feel the same, that it can become this like awful gaslighting type of situation.

C: Yes. Now kids get adopted and they know and there’s therapy and there is support and there’s online forums and there’s books on and on and on. As a kid that the intervention was we’re going to tell you that you were adopted and that was radical. So I had a lot of complicated feelings that I was dealing with growing up. I started having depression. My solution to all of that was to go all the way across to the United States. I was living in California. I grew up in California, go across the United States and go to college and get away from myself, which I learned that we can’t do.

A: It all follows. I think that is a common thing. I’ll change my hair. I’ll go to a different place. Maybe I’ll break up with this boyfriend and then everything will quote unquote, be perfect. There won’t be any problems. So that must have been really difficult when you realized, oh shoot. Everything came with me.

C: Yes. For me, I think trauma and my kind of mood instability, they’re really linked. There’s quite a bit of research on that, actually that for people who have kind of this genetic predisposition to a mood disorder or a thought disorder that trauma can often be the catalyst. A trauma or even ongoing trauma can be the catalyst to starting off something that maybe had there been different circumstances wouldn’t have happened or wouldn’t have happened so early.

A: I think a lot of parents maybe have the misconception, especially in those teen years where it is really challenging for the teen wanting independence just to be a grownup that it’s this misconception that they’re out of control or that they do potentially, because teenagers can have that affinity for repeating maybe the tantrum phase or things like that. I think so many of the times we get confused or we miscategorized, what is actually going on for our teen versus saying, maybe we do need to look for doctors, maybe we do need to look for mental health care, because it also is one of those things that as much as that conversation has moved forward so much compared to when we were growing up, it still is really challenging to find that solution. It’s not like you could just go to one doctor and go okay this is definitely it. And then have a smooth sailing path moving forward.

C: Yes, absolutely.

COLLEGE LIFE

A: Did you find that when you were in college that it was easier to find the resources at that point, or it’s still very challenging?

C: You know, I think college was the first time I realized there were resources kind of beyond what I had experienced as a younger teen, which was a doctor telling me to get more exercise and then a brief stint in therapy where literally the therapist told me I was possessed.

A: Like you just can’t make it up with some of these doctors.

C: Yeah. So I got to college and I got counseling. I got to work with professionals and then women in my age group to talk about sexualized violence and violence against women. It was really in this time, kind of the late nineties, where this was really starting to be a movement, starting to be a conversation about consent, about what does that mean? I was really a part of that. It was very healing for me because prior to going to college, I did a gap year as an exchange student and I experienced kind of an unwanted sexual interaction to which I clearly was not giving consent and kind of forced to participate in anyway. I carried a lot of shame. I didn’t know what to do with those feelings. I came home. It was like, who am I, what am I doing? Intimacy had completely changed for me. And then I got to college and it was like there’s a voice for this. We can talk about this. So it was so liberating in that way and so healing. I also did like movement studies and theater and I used that to actually express the work that we were doing on campus and just kind of in the larger community sexual violence.

BOYS WILL BE BOYS

A: I think that’s the biggest piece of it is being able to talk and being able to find that community so that it doesn’t feel as shameful or it doesn’t feel like it’s just you. It’s really horrific when you look at the stats of people that have had sexual assault experiences that it’s like one in four or in Canada.

C: One in three here unfortunately.

A: It really is that unfortunately when we look at law enforcement, we look at society’s perception of these crimes that it just it doesn’t align even now today, what it really needs to. So I think when you can find other people that say this happened to me, we’re going to be okay. And just have that acceptance of it or the acknowledgement of it I think it’s huge because society still wants to say boys will be boys. It’s horrific in Canada they just passed a law that if the person assaulting you was too drunk to know what they’re doing, then it’s no longer a crime because they just couldn’t control their thoughts or their actions. We seem to be moving the scale backwards instead of forwards, which is mind-boggling to me in 2022 that it’s not taken more seriously.

C: I think there’s a certain silencing that happens. We had the me too movement and people really came out to say like, yeah, happened to me too. I think then there has been a backlash against that and a shaming almost of like, oh you kind of silly women needing to talk about your, you know, bad sexual experience. When really it was just, two teenagers fumbling around and why do you have to make it a bad thing? Or, you know what were you wearing or who was drinking? All of those questions that society poses upon survivors. So, I mean yeah I’m sorry to hear that.

A: They’ve had a lot of backlash, so hopefully that’s something that changes. It’s a really fine line because also once law makers go down that path of either the boys will be boys, or I know in California when Brock Turner got a whole whopping three months in jail and all of these things that they set precedents, but they also create this situation where it gives us something to move forward and fight against to change. Hopefully with the louder voice in there, our ability to start movements a lot faster now, like the me twos versus 30 years ago, when we didn’t have the ability to have that technology to connect with each other as easily. I do think that we do have the ability to make more significant changes. It’s just slow moving. Always.

C: Absolutely. Yeah.

BEING HELD AT GUN POINT

A: Going back to your experience in college. So you were finding all of these different outlets, which is fantastic. Was there a professional that said even though all of these things are moving in the right direction and you are finding yourself and feeling a different way. When did the bipolar diagnosis come in?

C: Yeah, that’s such a good question. So it didn’t happen until I was 33. So I went to college. My experience was that I had healed a lot of my demons. I felt really empowered. I met my husband. We had children got married, you know, did the whole thing. I got a master’s degree while he was earning his teaching credential and we moved to the Bay Area and started our careers and kind of building our life. We had moved to the Bay Area. I want to say like six months prior, it’s kind of a weird situation. We had this little dog that we adopted and the dog would like to run away out the door. Like you have to be really careful opening the door because the dog would run away. It was like January. So, it’s dark at five o’clock when you get home from work.

A: For sure.

C: I opened the door and the dog ran out and so I chased him kind of unwittingly into kind of some bad neighborhoods caught him. We were walking back. I was almost back to the house and I’ve never actually had the experience that you read about where you feel somebody behind you, even though you can’t see them. I felt it. I turned around and it was this young person pointing a gun at me.

A: Terrifying.

C: Yeah. We were pretty close in proximity and it was just this moment of like, I didn’t have a purse. It was like what do you want? All I have is this dog that I have in my arms. It was just sheer terror. That was the first time I had really had an experience where in that moment, my life flashed before my eyes. I didn’t know if this person was going to kill me. So I put the dog down and just was like leap of faith and just turned around and ran to my house. And fortunately the person didn’t pursue the dog ran after me so we were safe. I think what happened is, with trauma, the nervous system and kind of the limbic part of us gets really primed and if we can recover and integrate and process those things and kind of move on and have a relatively, you know, life is always bumpy, but no big, like huge spiking traumas. Right?

A: Sure.

POST TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

C: I think my system over time had become very sensitive and primed to what would happen to me when that trauma occurred and it did occur and I kind of went into full blown PTSD. You can’t diagnose that for the first month after a trauma. But mine persisted. I ended up going to the doctor. I just got worse and worse and worse. I would go to work and I couldn’t stay. I would have these breakdowns and crying a lot flashbacks every day of this person holding me up with the gun. I went to my doctor kind of desperate, like what do I do? She prescribed an antidepressant, which totally makes sense. I was telling her like I can’t function at work. She prescribed me a low dose of an antidepressant. Within six weeks I was having kind of cyclical suicidal ideation, that I had never had before. Where I would literally be driving my car and suddenly want to crash into the car in front of me to cause damage to myself for sure. Other ideations and my mood was unstable. Like one minute I was just like life was grand. I felt in love with everybody. Like I was, you know, these anti-depressants are amazing. Then I was driving on the road, suicidal and I just, I was in it. I didn’t know like what was going on. I was just kind of trying to like get through the moment and the moment just got worse and worse until I woke up one morning and found a straight razor blade and started cutting my wrists kind of in a dissociated state. I don’t have a clear memory of it but it ultimately resulted in a hospitalization. It was there where it was suggested to me that possibly what I experienced while taking the antidepressant was more of a bipolar episode than a depressive episode because in unipolar depression, they don’t tend to see that extreme mood variability in response to an antidepressant.

A: It is really devastating I would imagine to be in that moment and to not really feel which way is up as far as not knowing what you’re going to expect every single day, as far as moods and stuff go. It must’ve been so scary to be experiencing that. I just want to drive off a cliff feeling for the first time, especially as somebody who has kids and a husband. I think a lot of times too, we think of, okay, if I have this disorder or I’m depressed or I’m anxious, I can go to the doctor they’re going to give me this one medication and then it’s smooth sailing. It kind of reminds me back to like the infomercials or the commercials back in like the eighties and nineties where it’ll cure one thing then it’ll show you just lists and lists and lists of all the side effects of it. It is really scary that when dealing with depression and anxiety, that one of the side effects commonly are those suicidal ideations and those negative, dark thoughts.

C: Yeah. That’s why there’s a black box warning on so many of these medications.

A: I also wish that black box warnings for things were so commonly transparently advertised because I feel like a lot of the times they will have a black box warning, but you won’t necessarily know about it until enough people come forward and take it to technology and complain about it that then the transparency be forced to happen.

RADICAL ACCEPTANCE

C: At that time it was kind of a suggested diagnosis. There wasn’t any clear, like you have this go forth into your life. It was more like, we’re not sure you had this weird reaction to an antidepressant. It’s probably not a good idea for you to take SSRI. Why don’t you try a low dose of Lithium? So I’m sitting there, like in the hospital talking to this doctor and my mind was just blown. I think it was sort of this cascade of like, oh my God, Lithium that’s that’s for like somebody who’s really severely, mentally ill. And is that me? And how am I going to make sense of my life? But I think the kind of constant refrain was I should’ve known, I should’ve seen me of all people being at the time. I wasn’t a licensed therapist, but I was on my way. I was working on my license, working in the mental health field. Like I should know better. It sounds kind of nuts, like saying it out loud. Like how could I know, how could I know better? I just had this guilt and shame. I felt so devastated and that’s really I’ve had to work on that for a very long time. I think I’m kind of coming into a different place with it, but even still yesterday I was feeling it because as time went on I had multiple hospitalizations and I was on, I don’t know how many I need to count it up. Actually I don’t know how many different medications I tried. I’ll see photos of myself during that time, everybody else’s like alive and smiling and I’m just flat in the picture and yeah, it’s like, oh my God, what happened?

A: If somebody else was going through a similar situation, even if they have the same education as you. I highly doubt that you’d be like, hey dummy, why didn’t you figure this out for yourself? Why did it take you so long? We would never talk to somebody else, or I would hope that we would never talk to somebody else that way that it is so hard, how hard we are on ourselves and how challenging those thoughts can become. Guilt is one of those things that it does take a very long time, if not a lifetime to let it go. Forgiveness for ourselves. I don’t know why it’s the hardest, but it absolutely is the hardest to let go. So I think it is just remembering to be gentle on ourselves. All we can do is know in that moment, that’s what we knew or that’s what we were being told and hopefully try to move forward from that step. But I definitely understand how challenging that can be.

C: I think what you’re talking about is for me, what I’ve come to describe it as is radical acceptance, which is part of therapy created by Marshall Linehan here in the United States called dialectical behavior therapy. Radical acceptance is also actually a Buddhist tenet of life. The idea is that we. As human beings suffer, we will suffer no matter what we do and trying not to suffer, causes more suffering. If we can like come into the moment and radically accept, okay, this happened. And that doesn’t mean I like it, or that it was good for me or that it didn’t destroy some part of me or my life or my family, or, you know, whatever it is, but it happened and now I have some choices about how I move forward until I can like, hold that in my body, mind and spirit that it did really happen before if I’m fighting with reality I can’t clearly see a path forward.

A: I think that would even be like, say going back to being adopted, being able to just say it out loud and have that acknowledgement does give it so much power, but also then does sort of release that pin of shame and secrecy and internalizing it.

C: Exactly. Yes.

MYTHS ABOUT PEOPLE WHO STRUGGLE WITH THEIR MENTAL HEALTH

A: Anybody who maybe doesn’t know somebody who has anxiety, depression, or bipolar disorder. What are some myths that you would like to see people shift their perspective on?

C: Well the first one that comes to mind is this vernacular that is used particularly to describe someone maybe who appears to have an unstable mood that wouldn’t necessarily be clinically diagnosable as bipolar, but people will sort of flippantly say, oh she’s so bipolar. Sort of like armchair diagnosing by a lay person who maybe just doesn’t like the behavior of somebody or who maybe can’t tolerate the intense emotions that someone is having or who maybe needs to kind of subjugate or make small the person that they’re talking about experience. So I really don’t like that. I think it’s pejorative. I think if someone is claiming or owning that diagnosis for themselves and that’s a conversation that’s different, but just to flippantly say that somebody is bipolar does not sit well with me.

A: I feel like we see that a lot on social media of oh I’m organized, I’m OCD. I’m having a bad day I’m just so bipolar. We do throw around those labels so flippantly, like you said and it is really disrespectful because it just doesn’t mean the same thing. We are really belittling people that do actually have a diagnosis by doing that.

C: Exactly. So I guess the myth buster that I would say here is that intense mood or even mood instability does not necessarily mean that someone has bipolar disease. It can mean a lot of things and so the best thing that you could do for that person is maybe gently suggest that they talk to a professional. It seems like you had a really big response to that TV show. Have you ever thought about talking to somebody rather than like telling your friend? Instead of I hung out with so-and-so and they’re so bipolar.

A: Yeah, it’s just creating that safe space for everybody, the way that you would expect somebody to do for you. And it is so cheesy to go back to that, you know, treat people the way that you want to be treated, but fundamentally that is a big piece of how we should function as a society.

C: Yeah, yeah. It is and I think there’s a lot of grief in the world right now for so many reasons. I mean, if I could distill it down in this conversation, I think it is about that, like that we are gentle with ourselves and with each other, and that empathy breeds vulnerability, which breeds more empathy rather than fear which can breed hostility and violence.

CHANGES IN COMMUNICATION STYLES

A: It has been so hard so whether it has been the last couple of years, or I think just even our shift and how we communicate, because I feel like a lot of the times you’re more likely to send a text or you’re send them to message through Facebook or any other social media channel than necessarily pick up that call and have in-person conversation that sometimes I do wonder if it’s just not harder to build those relationships that we had pre all of this technology.

C: I think so. I really think so. For some reason I’ve kind of interacted with several, for some reason their clients, but how do I know these people? I’ve seemed to interact with kind of teenagers and young people a lot recently. They talk about the pandemic specifically as being such a dark time. And particularly for teens who were, or are in high school they literally spent like a year and a half in bed.

A: I have a 15 year old and it was like going from night and day. It was from going from essentially not leaving their bedroom then to have to go back in and function in society as if nothing happened. This year has been extremely challenging. It’s so hard because educators or society as a whole can’t necessarily not function the way that it was before but they definitely need a lot more understanding and grace this year.

C: Yes. Yes, absolutely. I think any person in education on any level that I have talked to has talked about how difficult this year has been.

A: I don’t envy them at all.

C: No, they’re like they have no social skills. They don’t know what to do with themselves. They don’t know how to talk to each other. They don’t know how to be in a classroom anymore.

A: Or even just the idea of having to pay attention for six hours a day when they’re in really not used to doing it. All the teachers also have to try to cram essentially two years worth of curriculum in for them. So I know this will be a year that I will not be focusing on my daughter’s report card as much.

C: Yes.

PARENTING A CHILD WITH MENTAL HEALTH CHALLENGES

A: Do you mind talking about your child’s experience? You said they were starting to exhibit similar experiences that you were, do you mind talking about sort of what that ended up looking like or going forward?

C: Yeah, I don’t mind. My kiddo was in seventh grade when I started getting calls from the school counselor that friends were coming to the counselor and saying they were concerned about my child. It started out with finding out that she wasn’t eating. Which was like, okay I haven’t noticed that. I took her to a eating disorder specialist and things seem to resolve. So I was like, food and body image had been difficult for me kind of post that difficult sexual interaction that I had on exchange and so I really struggled with food and body and image for a couple of years. I was like, oh my, I know this, I see it, I understand it. I’m going to do all the things. We’re going to watch YouTube videos about eating disorders. We’re going to go to the eating disorder therapist. I’m going to make sure I’m going to check in and it really did seem to get better. A few months later, the counselor calls me again and it’s like you know, your child once again, the friends have come to the counselor, your child has been cutting and I went to the school and it was presented to me as a possible suicide attempt. So I decided to take them to be assessed I don’t know how it is in Canada, but here in the United States, if you’re having like a psychiatric emergency, you go to the emergency department.

A: So we have it similar here, or they also have if it wasn’t like in that moment, potentially like a suicide attempt, we also do have a mental health office where you can go get assessed and get linked with counselors and stuff like that too. So very bad emergency, very similar. Anything, a little bit less we have counselors or mental health that we would go a little bit different than our GP.

C: So this was a situation where I just wanted another set of eyes. I was really aware that my eyes were not going to be a professional eyes in this instance.

A: And they shouldn’t have to be. You should be allowed to take your psychologist hat off and just put mom hat on.

C: Exactly. So we went and they kind of got more information and determined that she was really suicidal and they hospitalized her. At that point, I’m just having like flashbacks of like my own recent experiences. Once again, the shame comes up of like you’re a therapist and here’s your kid struggling, and you didn’t even know to what extent it was happening. Here’s your kid cutting and you had no idea. So I’m berating myself again. We got through that and then she was given a depression diagnosis. We tried some different medications. Some of them really helped then unfortunately we found out that when she was 13, she was molested by a family member. So again, it’s like these echoes of experiences that I have had or causes that I have fought for. It was really difficult to kind of untangle that knot. Ultimately though I was a mom going through this with my family. So there was a second hospitalization that happened kind of out of that aftermath and then began a period of kind of post-trauma and gender exploration simultaneously. It was really difficult to like suss out what is happening.

A: And imagine with youth as a grownup, we can kind of say I feel this, or this is going on for me but young people, their brains aren’t even built enough to have that awareness within themselves to say, it’s this, this or this. So I would imagine that piece would be so challenging.

C: It was. I think because it all happened at the same time I think it’s different than if our child hadn’t been having all of these challenges and had just come out to us as you know, non-binary or transgender. That would have been it. We would have been down that path supportive all of that, but because it was all happening at the same time, there’s sort of, I think we were searching for this cause and effect like at this cause, this did that cause that, so kind of retrospectively nothing is perfect, right? This is why we have hindsight. But during that time, I think there were two hospitalizations and then what they call like it’s like a home for teens where they go and kind of live there and get group therapy, but it’s not a lockdown unit. It just became really clear that my teenager was suffering from PTSD mood instability that that was cyclical and had distinct episodes. And because of my diagnosis, I think there was just a general assumption that it was probably bipolar as well. We tried a lot of different medications. None of them really worked. We tried therapy. They hated every therapist that we’ve linked up with. Now they’re away at college and not on medication and doing really well. That happened after the book was over. So in the book, it probably sounds, it may come off as like, this was now my child’s sort of the bipolar diagnosis journey that they were going to be making in their life, but I don’t know I guess, we just don’t know what the future holds, but right now they’re doing well. I think it’s good that they went away to college and are having, young adult experiences away from home.

A: I think as moms, we do want to keep our children safe and bubble them and we really take a lot of that I should have seen, I should have done, I should have created all of these spaces for our kids. It is really hard when all of a sudden we realize, this is a separate little person that I don’t know what the friends know or they’re so good at hiding or compartmentalizing different aspects of their lives. That I think a lot of times as parents, we don’t have the ability to see it because they don’t have the ability to present it to us. They’re really good at putting on that happy home front. A lot of the times we do miss it. It is just hoping that we’ve created that safe space as they get older and they get more comfortable with themselves that they’ll tell us things. I would imagine that it’s so many other parents that have been in that perspective, that felt exactly the same way. Sometimes even, the eating thing I’ve noticed, with my daughter that this age, it was sort of the stress of I don’t feel hungry and it wasn’t until she had lost about like 10 pounds that I was like, oh wait, you’re becoming different. So it isn’t until they physically present it to us. I also think there’s maybe that misconception that once you’re diagnosed with bipolar that maybe your experience sort of a straight line of this is what happens and as your child has proven, maybe that’s just not the case. Maybe certain therapies do end up leading you on a different path that can lead to different happiness. It isn’t let’s throw pills at it and problem solved.

PUBLICALLY BEING A THERAPIST WITH MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

C: Yeah. Yeah. Currently I’m really in this place of like, I think because I decided to release this book under my own name, I’m essentially coming out as a mental health professional who has had trauma. I have a diagnosis and I have been in psychiatric wards and what that’s like that I’m really seeking to talk to other professionals who have the same kind of story maybe felt to them almost like a shameful secret that really doesn’t need to be and how do we as therapists, those who choose to, talk to our clients about the fact that we are humans and that we are allies and allyship sometimes means that we’re part of that group. I’m starting to see that trend. It’s tiny little droplets, but like on psychology today, now you can identify what groups you’re allied with. Person with a mental health diagnosis, who is a therapist, is not on the list. Not yet. However, I feel like we’re moving in a direction where if that is a therapist style, or if that is something that they feel like is part of their approach to working with clients then let’s talk about it. We’re trained not to talk about ourselves in session. I don’t know if that’s ultimately always the best choice for clients.

A: Well, I think it’s that connection piece. I think if you were suffering with something you want to know that the person that you’re talking to has had the experiences has gone through some stuff, I would imagine it just makes it so more comforting. I know my daughter went to a counselor and she asked for feedback. She was like, I want to get your advice. I want to know what I should do versus the and how does this make you feel? I think sometimes in a talk therapy there can be that pressure of are they going to judge me? Are they going to think of the same way? But I think that it does make it more human and we just want that human connection. I can see if it’s like little droplets of yes I’ve been through this or no you’re not alone versus massive stories during their hour or whatever the case may be but I do think that there should be allowed for more conversation or dialogue.

C: Absolutely. We definitely are seeing a trend towards self-disclosure is fine. As long as it’s in the best interest of the client. I do think though there’s a huge stigma in the mental health community unfortunately. I think because we have to talk about clients in this diagnostic shorthand we identify them by their problems, not their strengths or successes. You know, if we’re in a meeting and we need to talk about so-and-so who’s in crisis we’re not going to necessarily talk about like what a great mom they are for five minutes, but we’re going to talk about their suicidal thoughts and behaviors. I think that kind of engender is this like stigma of other it’s us and it’s them that has a necessary role. But I know for me, I can have what we call gallows humor about my clients, talking about so-and-so and their symptoms. And next thing I’m thinking is like how could I have even said that? Why are we having this humor? Obviously, you know, we need to get through the day. This is really hard work. I don’t know that it promotes breaking down that barrier of us in them.

A: Which all we can kind of hope for is having that awareness for it now and trying to move forward in that we have more connection. Now if anybody is wanting to work with you or find you on social media, do you have a website?

C: My author website is CaitlinBillings.com. I can be found on Instagram at @caitlin.billings.

A: Thank you so much, Caitlin, for having this conversation with me.

C: Thank you. This was wonderful.

Leave A Comment